Additional Information

White House history is a place where friends are long remembered, and among the most popular of those friends are the hard-working animals. In the nineteenth century presidential households relied on horsepower to function, but working animals, from dairy cows to honeybees, have also enriched life at the White House. With this issue of the Quarterly we turn to some of everyone’s favorite chapters in White House history, beginning with the American bald eagle, now officially our national symbol.

With her article “The Animal Envoy,” Elizabeth Margaret Rees shares the role of animals in diplomacy. Through such examples as pandas Ling-Ling and Hsing-Hsing, Rees explains that “the giving of animals is an expression of national culture and of goodwill.”

Rebecca Boggs Roberts takes us back to World War I when a picturesque and growing flock of sheep made their home inside the White House fence, keeping the lawns trimmed and saving on manpower, to help in the war effort. So appreciated was the work of the sheep that bids on their wool reached record highs at an auction for the benefit of the Red Cross. A sample is prominently displayed at the Woodrow Wilson House today.

Author Jonathan Pliska details how Pauline Wayne III, calved on July 15, 1906, and officially registered as number 115580 with the Holstein-Friesian Association of America, quickly became the most famous cow in America after she arrived at the White House to keep the household of President William Howard Taft supplied with fresh milk and butter. The press and the public were obsessed with her every move, but Pliska makes it clear that she preferred to be left alone.

Lauren McGwin shares an account of Siam, the first Siamese cat in America and a gift to First Lady Lucy Hayes in 1879. After crossing the Pacific Ocean by ship and America by train, Siam was described as affectionate and appreciative and intent on following Mrs. Hayes throughout the White House. McGwin reveals that her story ended too soon and with a mystery that may one day be solved.

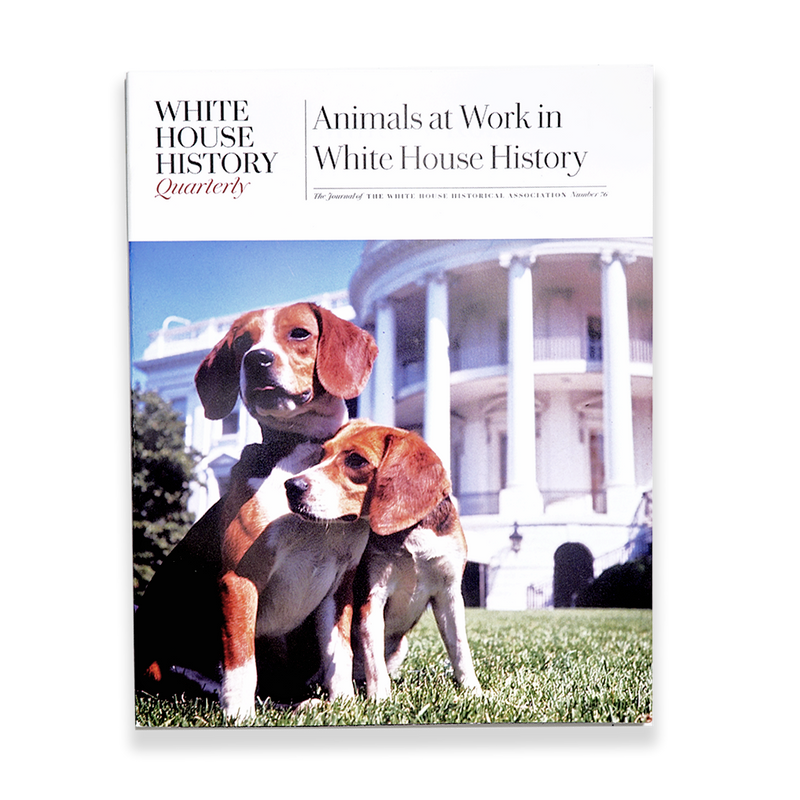

Colleen Shogan explains that even the first family pets can have jobs to do at the White House. With her article on “media hounds,” Shogan looks at the “first dogs” who made history as presidents capitalized on their pets’ popularity through media messaging. A favorite subject of White House reporters, these “first dogs” have made appearances in the Press Room, been featured in campaign materials, written books, and starred in films. And, with our Quarterly archival feature, Brittney Meadors shares a “paw-tograph” made by President Gerald R. Ford’s golden retriever Liberty, who set to work answering the mail by signing photographs with her own ink-covered paw.

For our Presidential Sites Quarterly Feature we go to the Reagan Presidential Library and Museum in Simi Valley, California, where wildfires are a continual threat to the facility. Jessie Kratz explains how thousands of brush-clearing goats have been put to work in an annual program to help mitigate that threat.

Stewart D. McLaurin closes the issue with reflections on “Continuity and Companionship” while remembering a few of the “first pets” he has known.